The world’s top chemical-weapons detectives just opened a brand-new lab

Created on 18 May, 2023 • Nature Scence • 176 views • 4 minutes read

The state-of-the-art centre will help to enforce a near-universal ban on certain chemicals and train analysts from around the world.

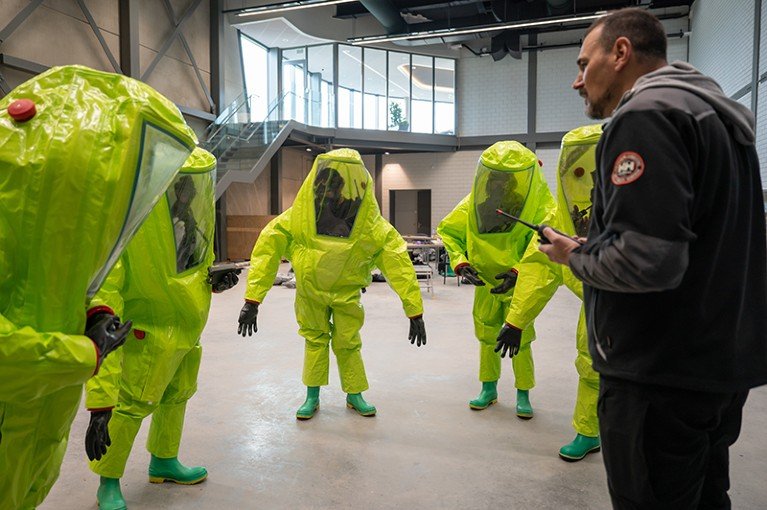

PCW inspectors are trained to use hazmat suits with a self-contained breathing apparatus.Credit: OPCW/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The international body that banned chemical weapons is due to celebrate its first major milestone sometime this year — the completed destruction of the world’s declared stockpiles of banned substances. But at the organization’s brand-new facility in the Netherlands, scientists from around the world will continue its work to prevent, spot and respond to chemical warfare.

On 12 May, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) officially inaugurated its new Centre for Chemistry and Technology near The Hague, where the international body will bring together its existing laboratories and add new monitoring and training programmes.

Attacks in UK and Syria highlight growing need for chemical-forensics expertise

Although nearly all countries — except Egypt, Israel, North Korea and South Sudan — have officially renounced the use of chemical weapons under an international treaty called the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), such chemicals continue to be used illegally. The OPCW has played a central part in the response to crises: its investigators found that nerve gas and chlorine were used in the Syrian civil war during the past decade, for example, and in 2018 an OPCW team investigated the attempted assassination of a Russian dissident in the United Kingdom that involved a nerve agent called Novichok.

Historic step forward

The centre “will allow the OPCW to enhance the [lab] verification regime through maintaining and developing our knowledge, skills and expertise related to chemical weapons”, says OPCW director-general Fernando Arias.

“It was an historic step forward for the OPCW today,” said Paul Walker, a vice-chair of the board at the Arms Control Association, a non-governmental organization in Washington DC, after attending the 12 May launch. Although the OPCW’s monitoring work had been going on for more than a decade, the Syrian civil war catapulted it onto the global stage. “That began the whole process of realizing that we needed [the OPCW to have] much more expansive and expensive labs,” says Walker, who attended the inauguration on behalf of an umbrella organization called the CWC Coalition.

The new Centre for Chemistry and Technology is an upgrade compared with previous OPCW lab facilities.Credit: OPCW/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

“I think it will be a big deal for the OPCW,” says Alastair Hay, an environmental toxicologist at the University of Leeds, UK, who has been an OPCW adviser and conducts outreach training for the organization. “The previous lab facilities OPCW had were really quite limited,” he says. The lab will also enhance the organization’s ability to train researchers, he adds. The centre was built outside the OPCW’s normal budget, with €34 million (US$37 million) of voluntary contributions from 56 countries.

Stockpile disposal

Since 1997, the OPCW has had a mandate under the CWC to monitor countries’ compliance with the ban, which required signatories to stop producing chemical weapons, to declare their existing stockpiles and commit to destroying them. The organization has so far certified the destruction of more than 70,000 tonnes of chemical weapons, and it received the Nobel Peace Prize for its work in 2013. Of the eight countries that disclosed the possession of such weapons, seven have completed disposal. The eighth — the United States — expects to finish destroying its stockpile (mainly artillery containing mustard gas and nerve agents) in the next few months and is thought to be the last country to do so.

“We estimate that a large number of old and abandoned chemical weapons still remain undiscovered around the globe,” says OPCW spokesperson Elisabeth Waechter. For example, large numbers of rusting Japanese chemical weapons left over from the Second World War still await safe disposal in China. “While it is the responsibility of countries to destroy them safely, OPCW technical experts can provide advice — and verify the safe destruction.”

The CWC also compels state parties to report the production of chemicals that have a dual purpose — compounds that have legitimate uses but can also be used either as weapons or as ingredients to make them.

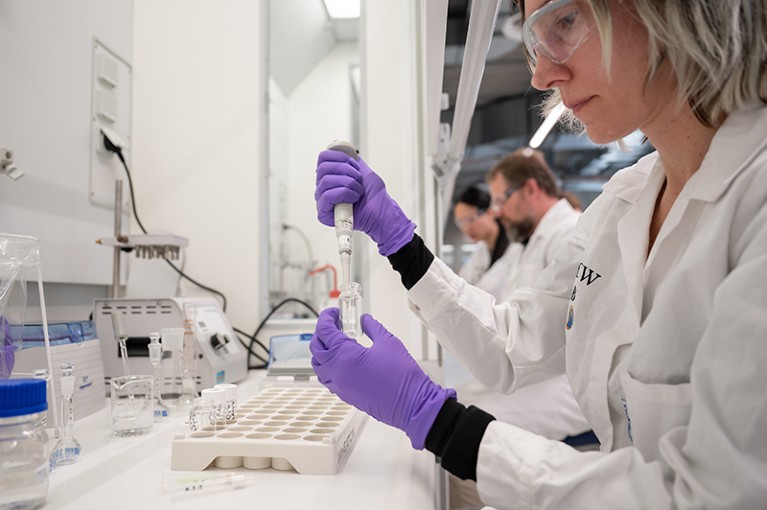

The OPCW analyses samples from chemical plants worldwide to search for evidence of the production of banned chemicals.Credit: OPCW/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The OPCW analyses samples from chemical plants worldwide to search for evidence of the production of banned chemicals.Credit: OPCW/Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

At the new centre, a warehouse is stocked with crates containing analytical-chemistry equipment ready to be dispatched around the world. As well as investigating alleged chemical-weapons attacks, the OPCW sends inspectors on routine missions to chemical facilities in member countries, often at short notice, to search for evidence of the production of banned chemicals. “Inspectors go to different sites and essentially audit what those particular sites have declared,” says Hay.

Samples brought back to The Hague are also sent to at least two international labs, to ensure that the results are cross-checked before they are reported to member countries. “It’s really important to be able to have access to really good facilities, where the results are incontrovertible,” Hay notes.

Novichok nerve agents banned by chemical-weapons treaty

These facilities are part of a network of 25 ‘OPCW-designated’ labs. The remit of the Centre for Chemistry and Technology includes putting labs through a periodic certification process to enable participation in the network. The centre also trains chemists from labs that want to match its standards and join the list. In an effort to provide knowledge to as many nations as possible, the OPCW is working on certifying labs in African countries for the first time: its current trainees include scientists from Algeria, Morocco, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa.

Increasing the labs’ geographical diversity can “build global capacity for the benefit of all regions and the international community as a whole”, Waechter says.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01622-9

Popular posts

-

Biolink WildlifeNature Scence • 236 views

-

-

The Best Smartphones for 2023!Shop Product Blog • 191 views

-

-